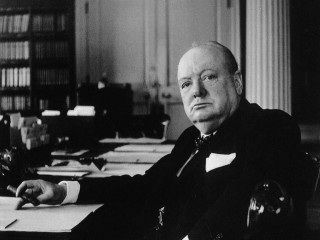

Winston Churchill biography

Date of birth : 1874-11-30

Date of death : 1965-01-24

Birthplace : Woodstock, England

Nationality : British

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-07-16

Credited as : Politician and statesman, prime-minister of United Kingdom, led Britain during World War II

9 votes so far

He is widely regarded as one of the great wartime leaders. He served as prime minister from 1940 to 1945 and again from 1951 to 1955. A noted statesman and orator, Churchill was also an officer in the British Army, a historian, writer and artist. To date, he is the only British prime minister to have received the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the first person to be recognised as an honorary citizen of the United States.

"Never give in! Never give in! Never, never, never, never, never--in nothing great or small, large or petty--never give in except to convictions of honor and good sense."

The English statesman and author Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill led Britain during World War II and is often described as the "savior of his country."

Universally acclaimed as one of the greatest statesmen who ever lived, Winston Churchill served Great Britain for over sixty years in various capacities, including prime minister during World War II. He was born on November 30, 1874, at his family's ancestral home near Woodstock, England, and died on January 24,1965, in London, England.

A poor student whose father feared he was intellectually challenged, an aristocrat who was reviled by many of his peers as a traitor to his class, a career politician who shouldered the blame for one of his country's worst military disasters during World War I and then went on to engineer its victory during World War II--Winston Churchill was an extraordinary man who time and again faced disappointment and adversity with courage, strength, and determination. He was a larger-than-life presence in his native England for more than fifty years and on the international scene for half of that, displaying a genius and vision that "made greatness casual and prodigious deeds commonplace," to quote a Newsweek reporter. To many, Churchill's death in 1965 at the age of ninety signaled the end not only of an exceptional life but of an era that produced leaders the likes of which we may never see again.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was the eldest of two sons of Lord Randolph Churchill, a British politician, and Jennie Jerome, an American heiress whose father was a noted Wall Street speculator and part owner of the New York Times. Born at Blenheim Palace, the family home of his ancestors, the dukes of Marlborough, Churchill was a child of privilege. But he was a sickly boy and a poor student who preferred games and play to school; only his father's influence gained him entrance to the best prep schools in England, including Harrow, where he consistently finished at the bottom of his class every term. He detested the rules and regulations governing life at Harrow and despised most of the subjects he was forced to study, except for English grammar and literature and debate and public speaking.

Churchill's grades were so poor upon his graduation from Harrow that it was clear he would never be accepted at Oxford or Cambridge. He did like to play with toy soldiers, however, and showed some talent and imagination in lining them up for battle. So Lord Randolph encouraged his son to apply to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, the West Point of England. After failing the entrance exams twice, Churchill barely passed on the third try (thanks to some intensive tutoring) and was assigned to the cavalry. At Sandhurst, he blossomed into an excellent rider and an eager student who devoured all the information he could about military matters. He graduated with honors in 1895 and was commissioned as an officer in the 4th Hussars, a cavalry regiment made up of gentlemen-soldiers known for their skill at war games and their love of "the good life."

Churchill soon grew restless and bored, and in late 1895 he asked for leave to go to Cuba, where a revolt against Spain was under way. He stayed for a few months, hoping to get a chance to fight but serving instead as a foreign correspondent for a London newspaper. Returning to England in 1896, he set off with the Hussars that fall for a lengthy stint in India, where he spent much of his first year or so playing polo and pursuing independent studies in history, philosophy, and economics. In search of more excitement, he joined a different regiment and this time saw action in a local rebellion both as a soldier and a war correspondent. His riveting reports from the front created a sensation back home, and in 1898 he gathered them into a best-selling book that led him to consider a career as a military writer. Later that same year, he served with yet another regiment in North Africa during the Sudan campaign, once again acting as both soldier and correspondent. Upon his return to England, Churchill resigned from the army to write another best-seller, this time on British military efforts in the Sudan. At the urging of some Conservative politicians, he also ran for a seat in the House of Commons but lost the election.

In the fall of 1899, war broke out between the Dutch Boers and the British in South Africa. Churchill headed there as a correspondent and was captured by the Boers not long after his arrival. In December, he managed a dramatic and dangerous escape from the prison camp where he was being held and eventually made his way into neutral territory. As news of his ordeal became known, Churchill was hailed as a hero, but before long he was being criticized for blasting the poor performance of the British military in a series of articles he wrote on his experience. Despite his views on the army, he soon joined up again so that he could get back into action in South Africa. After the war wound down, he returned to England and gave politics another try, this time defeating his opponent.

Twenty-six-year-old Churchill took his seat in the House of Commons in February, 1901, and immediately made a name for himself with his forceful opinions and penchant for siding with the Liberals on many issues (especially those dealing with social reform), a practice that angered his fellow Conservatives. Tensions gradually mounted to the point where Churchill left the party and declared himself a Liberal. He then served in a succession of government posts (which outraged many of his former Conservative colleagues, who accused him of selling out both his party and his class to realize his own ambitions), culminating in his appointment as first lord of the admiralty in 1911. In this position, similar to that of the U.S. secretary of the navy, Churchill was one of the few government leaders to recognize that Germany was preparing for war and that Great Britain should do the same. Although his warnings fell largely on deaf ears, he boldly went about the business of modernizing the Royal Navy and making suggestions for improving other branches of the service, even pushing for the development of a strange armored vehicle that was dubbed "Winston's Folly"--better known later as a tank.

On August 4, 1914, thanks to Churchill's foresight and perseverance, England entered World War I with the best navy in the world. The first lord of the admiralty remained intensely involved in military matters, even working out strategies with the help of various technical advisors. But in the spring of 1915 came a disastrous blow when combined British and French forces botched an assault on Turkish troops at Gallipoli, a peninsula that lies between the Aegean Sea and Istanbul, Turkey. Churchill had hoped that such an unexpected strike on the enemy's flanks would ease fighting on the European front and open the door to an invasion from the south. Casualties were very heavy, and outraged Britons unfairly held Churchill personally responsible for the defeat. He was forced to resign and take a lesser cabinet post, which he left some six months later after being excluded from a special war council.

Although he was still a member of Parliament, Churchill joined the army and served until the spring of 1916, at which time he returned to London on leave to participate in an official debate on the navy. Back in the House of Commons, he was subjected to a torrent of insults and abuse from his political enemies. But when his old friend, David Lloyd George, was asked to form a new government in July of that year, Churchill accepted his offer to mobilize Britain's industries for the war effort as minister of munitions. After the conflict ended in November, 1918, he was named minister of war and charged with helping British troops make a speedy and smooth transition to civilian life. He then served as secretary for the colonies and given the responsibility of ending Arab rebellions in Britain's outposts in the Middle East.

In 1922, Churchill lost his seat in the House of Commons following an election in which the Liberals were trounced by the relatively new Labour party. He ran again several times before he was finally victorious in late 1924, this time with backing from the Conservatives, who again embraced him as a member. During the two years he was out of office, however, Churchill was far from inactive. He wrote The World Crisis, a six-volume history of World War I, which was very well received. He also produced a number of landscape paintings, a hobby he had taken up to ease the tensions resulting from the Gallipoli affair. And he spent a great deal of time at his country house with his wife, Clementine (whom he had married in 1908), and their children.

Upon his return to Parliament in 1924, Churchill was appointed chancellor of the exchequer, the post his father had once held. As the man in charge of the economy, he angered British workers with his stubborn refusal to back down during a general strike in 1926. He subsequently alienated his fellow Conservatives for displaying the same quality in his dealings with them, and by the end of the decade he was again an extremely unpopular figure.

During the early 1930s, Churchill opened himself up to criticism as a warmonger for repeatedly warning in speeches and articles about the threat posed by Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. Pacifist sentiment was very strong in postwar England, and no one wanted to hear about the need to prepare for another conflict. To absolutely no one's surprise, he was excluded from the government Neville Chamberlain formed in 1936 and stood virtually alone in Parliament in opposing Chamberlain's policy of appeasing Hitler.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, a country whose borders England and France had pledged to defend. On September 3, following Hitler's refusal to withdraw his troops, Great Britain declared war on Germany. Reappointed by Chamberlain to his former position as first lord of the admiralty, Churchill immediately began assessing the status of the fleet. Meanwhile, things looked very bad for the allies during the first few months of the war as Denmark and Norway fell and the Soviet Union signed a nonaggression pact with Germany. Harshly criticized for his timid and inept leadership, Chamberlain resigned as prime minister in May, 1940, and King George VI asked Churchill to form a new government. Thus, at the age of sixty-five--an age when most people are looking forward to retirement--the somber yet determined statesman embarked on what would prove to be the most challenging journey in his life and in the history of his nation. "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat," he remarked upon taking office. "Let us go forward together with our united strength."

Churchill's first months as prime minister continued to bring nothing but discouragement. Holland and Belgium fell to the Germans, and trapped British troops retreated to Dunkirk in the north of France. In May, 1940, they braved constant bombing attacks while fleeing across the English Channel on anything that would float. Although much of their equipment had to be left behind, more than three hundred thousand soldiers managed to make it back safely, scoring a moral if not a military victory for the British. But just a month later came frightening news of the fall of France. Great Britain now stood alone against the Nazis, almost certainly the next target for invasion.

That entire summer of 1940, from late June well into September, the country was subjected to the "Blitz," Germany's savage and relentless air war. Bombs rained down on England, especially London, as Hitler tried to undermine British resolve, despite the prime minister's assertion that his nation would "never surrender." Donning a special "siren suit" of his own design, Churchill regularly ventured out into the streets of London after (and sometimes during) air raids to tour bomb sites and offer moral support to the local residents. They in turn welcomed the man they affectionately called "Winnie" with warmth and cheers, marveling at his gallantry, unflagging optimism, and total lack of fear. Thus did Churchill successfully rally his citizens to the cause and instill them with confidence during an extremely difficult period, which he described as "their finest hour."

When he was not busy bolstering the spirits of his fellow Britons, Churchill--an impatient perfectionist with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of energy--was directing virtually every aspect of England's war effort. He personally ran the army, navy, and the air force and never hesitated to become involved in other areas that interested him, an unorthodox style of management that nevertheless had the full backing of the country. He frequently traveled to the war zone to confer with military commanders and also met regularly with other world leaders, forging an especially strong bond of friendship with President Franklin Roosevelt in the months before the United States entered the war.

By late 1941, however, the British press had begun to question Churchill's suitability for the job of prime minister, suggesting that at sixty-seven he was too old, particularly if he insisted on running everything. Despite the fact that both the Soviet Union and the United Sates had entered the war against Germany, things continued to go badly for the Allies. In the Pacific, Japan had already captured Malaya, Burma, and Singapore and was sinking one major American and British ship after another. In North Africa, the Germans and the Italians were defeating the British and inflicting heavy losses. Equipment was in increasingly short supply, and the United States was unable to help because it was facing enough of a struggle supplying its own troops.

A humble Churchill decided to go before Parliament and ask for a vote of confidence in his leadership. He frankly expressed his opinion that things were going to get worse before they got better, but he reiterated his belief that Great Britain and its allies would eventually win. By a vote of 464 to 1, members of Parliament reaffirmed their belief in "Winnie" and his ability to lead the nation.

As Churchill had predicted, the setbacks continued well into 1942 as the Allies sustained heavy losses in the Pacific, North Africa, and along the Russian front; German U-boats wreaked havoc in the Atlantic. But in October of that year, the tide began to turn in North Africa following the British victory at El Alamein and a subsequent invasion by British and American troops. By mid-1943, additional victories had made it clear that Germany was slowly on the way to defeat. Then came the Allied invasion of Europe on June 6, 1944, and almost a year later, on May 7, 1945, Germany's surrender.

While the end of the war brought a tremendous sense of relief to the embattled populace of Great Britain, it also allowed old political rivalries to resurface as the need for cooperation evaporated. In addition, despite their great personal affection for Churchill, most Britons were tired of the Conservative party, which they held responsible for the war. Eager for fresh faces and fresh ideas, voters turned out Churchill and his party in July, 1945.

Coming as it did at a time when he was still savoring the Allied victory in Europe, this rejection deeply wounded Churchill, who took it as a sign of ingratitude. He reluctantly "retired" to his country estate and once again took up painting and writing, compiling a six-volume history of World War II that is considered a standard reference work on the subject. But he remained active in politics, too, both on the national and international scenes. He was especially outspoken on the subject of the Soviet Union and constantly warned about the dangers associated with the spread of communism throughout Eastern Europe and beyond. In March, 1946, during a speech in Fulton, Missouri, Churchill added a new phrase to the language when he described how nations under Soviet control were imprisoned behind an "Iron Curtain" that had cut them off from the rest of the world.

By 1951, Britons had grown tired of the Labour party, which had been unable to deliver on most of its promises of a brighter future. Voters again turned to the Conservatives, and at the age of seventy-seven, Churchill assumed the post of prime minister for the second time, serving until he voluntarily resigned in 1955. Now Sir Winston--he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1953, the same year he also received the Nobel Prize for literature for his book The Second World War--truly entered retirement, still technically a member of Parliament but basically no longer active (or even interested) in politics. He spent most of his time in the country surrounded by his children, his grandchildren, his dogs, and his racing horses, painting and puttering and gracefully accepting the numerous honors that came his way, including the distinction of being named the first honorary citizen of the United States.

On January 15, 1965, the ninety-year-old statesman suffered a stroke. For nine days he clung to life, but early in the morning of January 24 came word that he had died at his London home. Tributes poured in from throughout the world, for as a Newsweek reporter noted, "there was the feeling that somehow Winston Churchill had a hand in shaping the course of virtually every life. He was the one man who had infinite confidence when few others could see any reason to hope at all. He was the rock that could not be shaken." After a state funeral of a scale and splendor usually reserved for monarchs, Churchill was buried on the grounds of the parish church near his birthplace.

With the death of one of the last great figures of World War II came a sense that the world itself had changed in some way, that the era of such personally powerful and dynamic leadership had also ended. As a writer for Time put it, "Today's rulers seem, in comparison, faceless and mediocre. Churchill was an aristocrat, a brilliant dilettante, a creator in a dozen roles and garbs. He was a specialist in nothing--except courage, imagination, intelligence. He was never afraid to lead, and he knew that a leader must sometimes risk failure and disapproval rather than seek universal acclaim." Concluded another writer for Time: "If Churchill was sometimes wrong, on the great issues of his times he was most often right. History will forgive his faults; it can never forget the indomitable, imperturbable spirit that swept a people to greatness."

June 9, 2009: The U.S. Librarian of Congress announced the recognition of Churchill's March 5, 1946, speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, as a culturally significant recording to be included in the sound archive of the National Recording Registry.